6 minute read • published in partnership with Albright IP

Feature: Financial compensation for intellectual property infringement

An intellectual property right is fundamentally a right to prevent competitors from using your brand, invention, design, copyright work, or whatever. But what if they do? Frederick Noble, UK & European Patent Attorney at Albright IP explains.

A rightsholder who successfully sues for infringement will be able to obtain an injunction – a court order preventing the infringement from continuing. For infringements which have already occurred, there will usually be an entitlement to financial compensation.

Damages or profits?

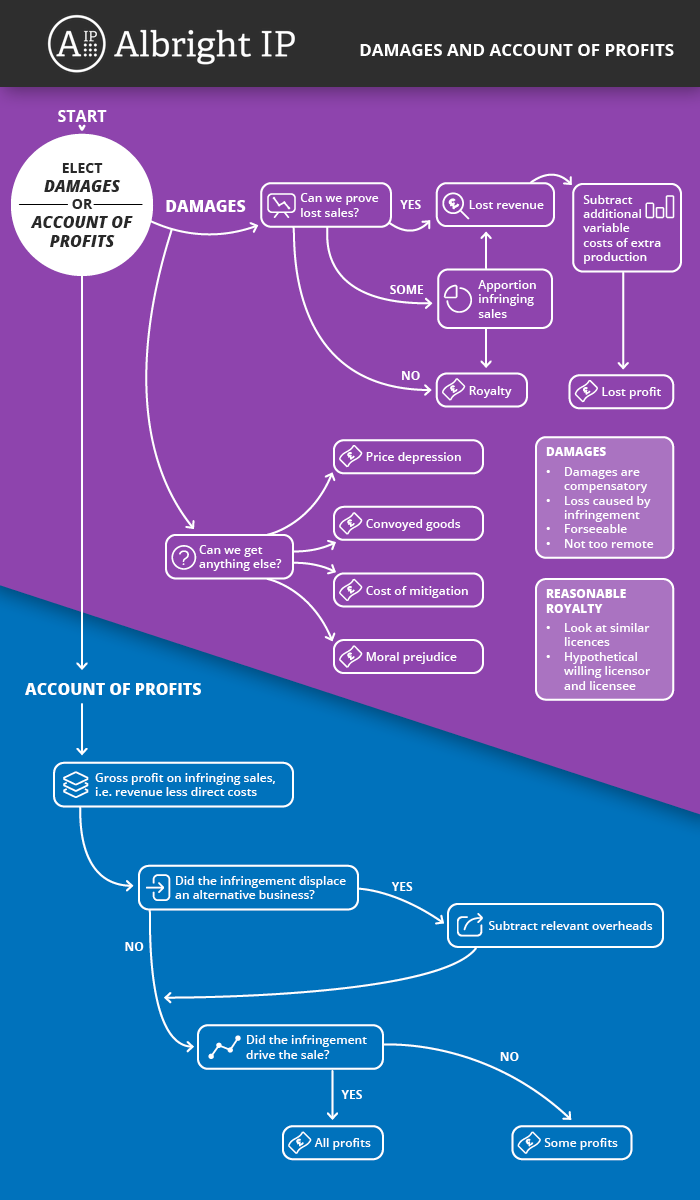

A successful claimant will be able to choose either to claim damages – compensation for the loss that they have suffered due to the infringement, or an account of profits – the profits wrongfully made by the infringer. The claimant will obviously want to choose the remedy worth the most and will normally be able to get an order for disclosure of the defendant’s documents in order to gauge the relative value of each option.

A rightsholder who successfully sues for infringement will be able to obtain an injunction – a court order preventing the infringement from continuing / Picture: Getty/iStock

Damages – lost sales

In theory, damages are compensation paid to a rightsholder for the loss caused by the infringing activity. A certain number of infringing sales will have been made, but a key question is whether all of those infringing sales represent lost sales to the rightsholder. All sorts of factors will need to be taken into consideration. As an example, if a counterfeit or pirate product is sold at a much lower price than the original, and customers probably know that they are buying a counterfeit, then it may be very difficult to say that all of those customers would have paid full price for the genuine article if the infringement was not available. On the other hand, if it is a very good counterfeit and sold at a similar price, so that customers are misled, then each infringing sale probably does represent a lost sale on the part of the rightsholder.

This example of counterfeit goods is relatively straightforward. In other cases, for example a patent infringement, it may be that nobody is being misled, but a rightsholder might still argue that at least a proportion of the infringing sales represent lost sales on their part. Evidence for this may end up being a little inexact. Again, multiple factors will come into it – the price of the product may be an issue; if the infringing product has aesthetic differences then perhaps some customers would not have bought the patent holder’s product just because they did not like it, and so on. In the end a Judge will have to weigh up all the evidence and come to an approximate view as to how many sales were lost by the rightsholder.

Damages – reasonable royalty

What if a rightsholder can’t prove lost sales for some or all of the infringements? They are still entitled to a “reasonable royalty”. This is an amount determined by looking at how much a hypothetical willing licensee in the position of the infringer would have agreed to pay a hypothetical willing licensor in the position of the rightsholder. Again it is all a bit – well – hypothetical, but relevant evidence might include similar licences in the industry. For example, in “simple mechanical” patent cases, reasonable royalties often seem to be determined at about 5% of sale price.

Reasonable royalty damages often end up being a small fraction of damages for lost profits, so rightsholders will work hard to try to prove lost profits for as many sales as possible, if they think they can.

Infringement of an intellectual property right is in a sense an invasion of the property belonging to the rightsholder. There is recognition that this cannot go uncompensated, even in cases where the rightsholder can point to no other material difference in their position as a result of the infringement. “Reasonable royalty” damages are the manifestation of this principle.

Other heads of damage

Any reasonably foreseeable damage caused by the wrongful infringement can in theory be recovered. Rightsholders may put forward various theories that they have lost out in different ways and need to be compensated. A few examples include damages for price depression, where a rightsholder claims that infringing activity has forced them to drop their prices; lost sales of “convoyed goods”, i.e. goods not specifically covered by the relevant IP right but which are typically sold alongside and provide additional revenue; and costs incurred in mitigating damage, for example the cost of additional advertising to counteract lost business caused by the infringement. Expenses associated with investigating infringements (separately from recoverable legal costs) may also be compensated ¹.

For intellectual property infringements that have already occurred, there will usually be an entitlement to financial compensation / Picture: Getty/iStock

Moral prejudice and damages for “flagrant” infringement

The Intellectual Property (Enforcement, etc.) Regulations 2006 ² provide for damages awards to take into account “non-economic” factors, such as “moral prejudice”. What is that? There is relatively little guidance so far, but it probably allows – in principle – damages for “pain and suffering” and “mental distress” caused by an infringement. English Courts have been rather reluctant to award damages under this head.

In copyright cases, “additional damages” can be awarded for “flagrant” infringement, and these additional damages can be quite valuable. Additional damages go beyond the compensatory principle and can be well worth claiming.

Account of profits

What about the other option – an account of profits? In principle, the rightsholder is entitled to the profits which the infringer has made by infringing, most obviously by selling infringing products. In the first place this is an accounting question – what profits have actually been made by selling this particular infringing product line? This might be less than straightforward, and there could be disputes over the proper allocation of variable and fixed costs. Then what about the central overheads of the business? Whether these can be properly deducted can be a contentious issue. The legal test is (a) whether the overheads would have been incurred anyway even if the infringement had not occurred and (b) whether the sale of infringing products would not have been replaced by the sale of non-infringing products. In other words, would the same overheads in fact have sustained a non-infringing business if the infringement had not occurred? ³. What this boils down to is that the rightsholder is entitled to recover the extra profits the infringer made due to their choice to carry out the acts which infringed.

Overall the rightsholder is entitled to the profits due to the infringement, so that may also raise the question as to whether the fact of infringement was really driving the sale of the product – i.e. did the consumer want an infringing product, a product having the particular characteristics protected by the IP right, or did they just want a product of a certain broader category? If the infringement did not drive the sale then an apportionment may be made so that the rightsholder is only recovering the profits due to the infringement, rather than all of the profits due to sales of the infringing goods.

In some cases what this can mean is that after all this difficult accounting, an account of profits comes down to more or less the same thing as a reasonable royalty, which is the least a rightsholder can expect if they elect to claim damages. Probably for that reason, damages tends to be the more popular choice. It does all depend on the circumstances though.

An enquiry into damages or an account of profits is the very last thing that happens in IP litigation. But it is well worth both parties having a good look at the possible financial implications early in the process, because with a realistic idea of the value of a claim, a swift and agreeable compromise can often be reached, vastly reducing the legal costs of resolving a dispute. Estimating damages can be complex, but we’ve made a handy flow-chart to help a little bit. Also, we would obviously be delighted to advise further on your specific case.

¹ See for example PPL v Reader [2005] EWHC 416 (Ch)

² Which implemented EU Directive 2004/48/EC and now form part of “retained EU law” following Brexit

³ See Design & Display Ltd v OOO Abbott & anr. [2016] EWCA Civ 95