5 minute read • published in partnership with Albright IP

Insight: Ownership and commercialisation of an invention

Intellectual property rights do exactly what they say on the tin. They are property rights which arise from the fruits of intellectual labour. But, where does ownership of an invention lie, particularly when it is part of a commercial endeavour? Dr William Doherty from Albright IP explains.

In patent law, ownership originates at the point of invention, that is, the genesis of the idea that forms the basis of any patent application filed. An inventor is, by necessity, a human, a position reiterated with the UKIPO’s DABUS decision – an artificial intelligence is not a viable inventor within the meaning of the UK Patents Act.

Assessment of inventorship is (somewhat) straightforward – any person who has contributed to the underlying inventive concept claimed in a patent application is by definition an inventor. An inventor is thus entitled to be named as such on a patent application, and inventorship is a non-transferable concept.

Ownership of the rights in the patent application stems from this original principle. However, it is worth remembering that property rights themselves are transferable, which is how companies, for instance, are capable of ownership of patents and patent applications.

Any person who has contributed to the underlying inventive concept claimed in a patent application is by definition an inventor / Picture: Getty/iStock

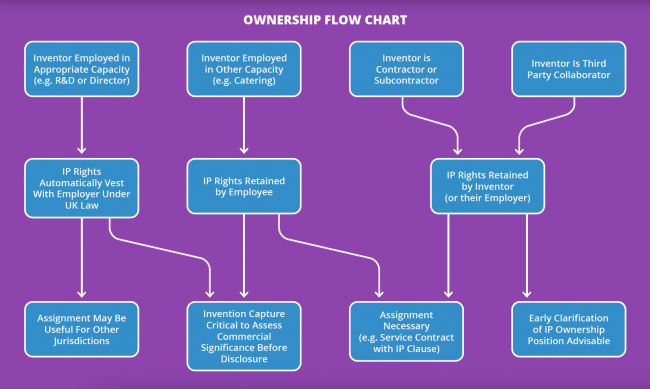

The way in which ownership is assessed can become quite convoluted and can be an extremely thorny topic to unpick after the fact. As such, it is worth considering the flow of ownership to ensure that, when you apply for patent rights, you take the correct decisions whereby the rights vest where you expect.

Derivation of right

There are a few primary ways in which patent ownership can arise:

1 – An inventor free from obligations to transfer the rights will retain ownership;

2 – An employer of an inventor who is employed in a relevant capacity (e.g. R&D), is under UK law, the automatic entitled party. No formal transfer is required from the inventor in this scenario; and

3 – The patent rights can be formally assigned from the inventor, or indeed any subsequent owner, to another legal entity.

How to hold onto your rights

The difficulty for a company is ensuring that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to ensure that rights are accumulated without leaving open the possibility of later entitlement actions, either from inventors, contractors, or collaborators.

The most comprehensive answer here is to ensure that all parties involved in invention generation on behalf of the company provide a formal written assignment of the rights into the company name.

Whilst it is possible to rely on the automatic entitlement provisions with regards to employee inventions, these provisions are not necessarily applicable to all employees. Furthermore, some jurisdictions do not recognise the derivation of right automatically; the US is a notable example here.

A culture of ensuring that assignment documents are in place for all inventors, ideally on an invention-by-invention basis, will help to avoid issues with entitlement disputes downstream. This is, of course, burdensome from an administrative perspective, and therefore it is worth considering inserting specific IP assignment clauses into employee contracts and service agreements with external contractors.

Graphic: Albright IP

Collaboration with other parties complicates matters further. If an invention has been made jointly with, for instance, another company having their own inventor employees, then joint ownership complications may well arise.

Whilst joint ownership is not, in itself, problematic, if IP is business-critical, then it is advisable to try and come to an agreement with the other parties involved to attempt to obtain full and sole ownership of the rights. That will allow for unencumbered sale of the company in due course, for instance.

There are many pitfalls which can arise in respect of patent entitlement which may not be apparent for a company conducting research and development, but with careful consideration in advance of filing patent rights, expensive issues can be resolved early on.

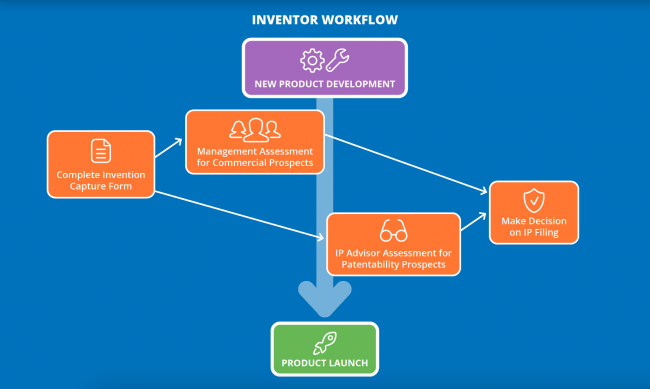

Invention capture

The most rigorous MD may have a cast-iron method of ensuring that all rights vest with the company, but sometimes it is the ‘unknown unknowns’ which are the real problem. How do you know what inventions are being generated within the company to lay a claim to, and indeed, how do you assess which inventions are commercially worthwhile?

This effectively encompasses the concept of invention capture; making sure that all important rights are tied down before the marketing department plaster social media with all of the latest snazzy developments.

Graphic: Albright IP

Education in research and development roles is absolutely crucial. Technical staff need to be aware of and actively engage with a formal process for recording new inventions prior to any form of public or non-confidential disclosure.

An indicative process might involve the use of a dedicated invention capture form (and here at Albright IP, we can provide templates for you to use in-house) which can be completed by researchers to capture thoughts on the way to full inventions being created.

The use of a dedicated form allows for company management or relevant decision-makers to make a determination as to whether the invention is business-critical, and therefore warrants protection. Simultaneously, your IP advisor can provide detailed feedback on the prospects for protection.

Without the initial invention capture, the intermediate assessments cannot be made, and crucial decision-making opportunities could be lost by inadvertent disclosure of innovative products prior to filing IP rights.

The two-strand approach

A complete overview is important here when considering how best to develop an IP protection strategy:

• Are important IP rights owned by the correct legal entity?

• If not, how best can this be resolved? Proactive assignment or agreement can prevent disagreements which may not manifest for many years.

• Are important IP rights being identified and decisions being made about protection?

• If not, should a cultural shift be considered to better capture inventive concepts and review protection protocols?

Sometimes, it can be difficult to determine the answers to these questions objectively. An IP Audit can be an effective tool in this situation to identify ways in which IP strategy can be improved within a business, in order to maximise the value and potential of your IP.