5 minute read

Opinion: There is more to manufacturing investment than shiny new machines

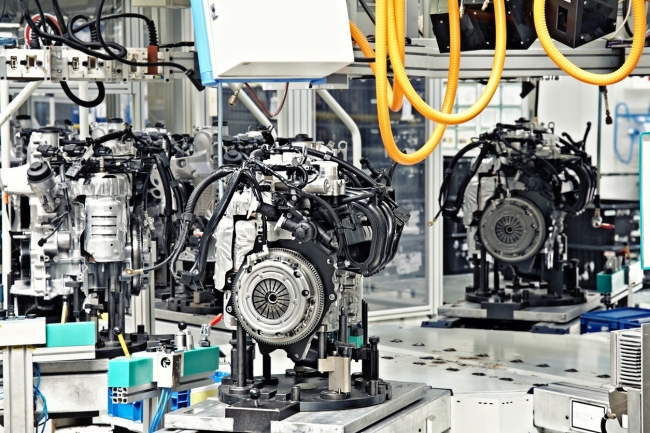

Investment is arguably the best health indicator for manufacturing, especially as more of the labour components in this sector are being automated and rationalised. But it can be hard to get a really accurate picture of actual manufacturing investment. There are different KPIs and some surveys are forward-looking (asking companies for their intention to invest, which of course can change), while others measure what has happened. Helena Sans from Barclays makes the point that measurements for investment in the manufacturing industry need to be scrutinised to get the full story.

As the Brexit deadline approaches, investment will be scrutinised harder as a measure of business confidence in post-EU Britain.

We often assume that investment in manufacturing means capital expenditure – i.e. new machines and equipment. But investment need not only mean new machines; should it also capture big maintenance and overhaul programmes that can refurbish some plants to “good as new” standards (admittedly, a contentious claim – it depends on the condition of the plant!).

Investment is arguably the best health indicator for manufacturing, but it can be hard to get a really accurate picture of actual manufacturing investment / Picture: Getty/iStock

And what about buildings – factories and extensions? And should all investment surveys measure “intangibles” i.e. skills? The deficit in many engineering and manufacturing skills is well-documented. A business might spend no money on capex but increase training of operational staff. Productivity rises and yet there are no new machines.

Look at the bigger picture – looking at year-on-year changes in investment does not always show what’s happening in real-time

There are big vertical sector differences. One sector might have invested hundreds of millions in capex in a year while another might only see big investment programmes in five year or longer cycles. The survey might miss that cycle.

For example, this year the UK automotive sector is down on total investment since 2015 by 70 per cent or more. This might ring alarm bells normally, but the industry would never sustain the record capital injection of £2.5 billion that automotive spent in 2015 every year – it is largely cyclical. Maybe we should compare the five and 10-year cycles side by side with the quarterly and annual surveys to get a fuller picture of investment.

New factories could be seen as a separate, legitimate indicator for manufacturing health / Picture: Getty/iStock

Industry trends show a change in the types of investment

The quarterly CBI Industrial Trends Survey in July showed that “investment intentions” in manufacturing deteriorated markedly in the three months to July.

The CBI research showed that planned spending on machinery & equipment is expected to stabilise over the year ahead (+4 per cent, from -8 per cent in the three months to April) but investment plans in buildings were scaled back (-14 per cent, compared to no change (0%) last quarter).

EEF’s Investment Monitor 2017/182 shows a different fall in investment intentions. This survey measured capital equipment specifically, with an emphasis on industrial automation equipment. It showed that average investment in plant and machinery in the last two years is 6.5 per cent of turnover, as opposed to 7.5 per cent in 2016. It also said that 40 per cent of companies said they had no need for more investment.

So while the CBI says planned spending on machinery and equipment is expected to stabilise, i.e. remain the same, no-one is expecting a capex spending spree and we expect both buildings and training investment will fall.

As economists analyse industrial investment, as well as the intangible measure of training I think they should also look at factory investment and potentially capex refurbishment too.

Accounting for new factories isn’t as simple as it seems, despite its importance

“New factories” does not always show up in a search for manufacturing investment, although the CBI’s Industrial Trends captures buildings investment. This could be seen as a separate, legitimate indicator for manufacturing health. New building data is not readily accessible – accurate numbers would need research with the planning departments of councils and HM Land Registry. Anecdotally, however, social media reveals some interesting observations.

The Twitter account Jefferson Group, @Jefferson_MFG with 30,000 followers, is a great, accessible source of new factory news. Considering that Brexit is looming, in 2018 the number reported by Jefferson is about three new factories per week, more if you include extensions. “Reviewing these announcements, I would say with confidence there have been at least 100 brand new build factory announcements nationwide since Christmas 2017, to mid-August, and probably a further 50 factory expansions on top,” said Stuart Whitehead, founder of Jefferson Group and overseer of the account. The money comes from both British and foreign companies; in fact Jefferson often summarises the week by focusing on the foreign companies investing money in the UK.

“After eight months in 2018, or about 32 weeks, that works out as 4.7 per week or about one per day. Its’ not the same frequency as 2017 but it’s still remarkably high. I have followed this sector closely for over 20 years and I have not personally observed such a strong run on new factory construction before,” Stuart added.

He accepts that social media and more news websites today mean that more of these stories are reported now, or are easier to search for on the internet than 10 years ago. And there can be a risk of double-accounting, where the factory is announced and then reported again when it is opened.

The CBI says plans for building investment are down 14 per cent in its Q2 survey. Therefore, if we want to 1) take factory investment as a separate measure of manufacturing health and 2) claim there are more factories being built now than pre-EU referendum, we’d need a deeper analysis.

Don’t dismiss the highly important metrics of investment in training and new factory construction as well as plant and equipment purchases / Picture: Getty/iStock

And don’t forget skills

It’s also interesting to ponder how the skilled labour market links with factory investment. Say there was a spike in investment in new, Industry 4.0 capable manufacturing technology, but there was no corresponding rise in I4.0 training spending. Would much of this brand new kit sit idle, while companies ploughed on with their Industry 3.0 machines? Surely both capex and training are mutually dependent to affect productivity.

Also think of essential, less frontline jobs than machine operators, such as HGV drivers and forklift operators. We know that applications for both these jobs in the UK are falling – (it’s the subject of a Barclays’ special feature in early November). A brand new factory is less effective on manufacturing output if either it only has half the number of forklift drivers it needs, or sucks these drivers from their existing jobs at other companies.

If training showed an upward curve, then a stable or falling capex trend in manufacturing would be less concerning. Conversely, if both capex and training were shown in decline, any anecdotal signs of more factory investment would be of little comfort.

Summary

Despite the ease of Google searches, the question is whether 150 new factories and expansions in eight months, for an economy of the UK’s size in a pre-Brexit year, is high, normal or low. Personally, I don’t know. But it is certainly very notable and encouraging that, more than two years after the EU referendum result, companies are still building plenty of factories in Britain. And the Jefferson Twitter feed shows that these investments are international.

For example, on August 9th the feed reviewed the week’s factory investment (this is August remember) and showed Japanese G-TEM (150 jobs) and US consumer goods giant Proctor and Gamble (£25m R&D centre) were among the investments. German, Dutch, Swedish and Spanish companies are among others building factories in the UK.

So watch capital expenditure in manufacturing, but don’t dismiss the highly important metrics of investment in training and new factory construction as well as plant and equipment purchases – these may paint a different picture to plant alone.